By Biyi Orilabawaye

Ordinarily, the passing of Baba Simon Olatuyi Odogbo should have been an occasion of celebration—a grand display of the rich and beautiful heritage of my people, blending the cultures of Edo and Ikale. Alas, his burial rites will instead be marked by heavy hearts and concealed bitterness.

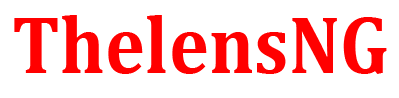

Baba Olatuyi Odogbo lived beyond a century, crowned as Laba in 1956 and formally gazetted on July 7, 1960, as the Paramount Ruler of Akotogbo. Yet, his reign ended in betrayal, callously and cunningly usurped by the very people he personally signed their appointment letters!

Baba Laba was a young bachelor working with Tribune Newspapers in Warri when he was called to ascend the throne after the demise of his uncle, Oba Nenuwa Aribo. He left everything—career, ambitions, personal dreams—sacrificing his entire life in service to his people. May history be kind to him.

The very name Akotogbo is a distortion of Eko Edobo—a name steeped in history. Edobo was a warrior; Eko means settlement. The British, in their colonial reshaping, twisted it into Akotogbo. Historically, this land was the undisputed domain of the Laba and his people, migrants from Benin since the 15th century.

A prominent Oba in Ikaleland once told me candidly: “It’s an open secret that your people, who migrated from Edo, are the original owners of Akotogbo.” He spoke the truth. The evidence is undeniable—the land configuration, historical artifacts, and colonial establishments such as the Court, Police Station, Post Office, and UAC office (with land records dating back to 1929), as well as relics like the British “Rest House.” During the colonial era, Akotogbo was grouped under Benin’s administrative authority within the so-called Benin Confederation, alongside Ajagba and Ujosun. Oba Simon Olatuyi himself once chaired meetings of the confederation’s Obas during the Western Region era in Ibadan.

The late Laba was a simple, trusting man. He placed unwavering faith in historical truth and the rule of law. Sadly, he was betrayed by those whose appointments as Chiefs he himself endorsed. His belief in an incorruptible judiciary proved tragically misplaced. In the end, he learned—as we all must—that only the Court of Heaven is flawless. Before our eyes, the paradox of Ecclesiastes 10:7 unfolded: “I have seen servants upon horses, and princes walking as servants upon the earth.”

History is clear on the origin of Larogbo: “Abodi left Benin with some Chiefs and settled at the western side of Owena, first at Arogbo-Ile. When leaving, he instructed Larogbo to take charge of Arogbo.” Arogbo has never been Akotogbo! The name Arogbo derives from Aro (canoe) and Ugbo (land)—a place where canoes are carved. How, then, did Larogbo of Arogbo metamorphose into Larogbo of Akotogbo? What became of Itarumo? The judiciary must forever answer for this injustice, and the Abodi of Ikaleland cannot turn a blind eye to this anomaly—this perversion of justice—against the Oke Ado people of Akotogbo.

Across the world—in Europe, America, and here in Canada—indigenous people are treated with dignity and protected as aborigines whose lands hold the roots of prosperity. They enjoy recognition, grants, and social privileges. They are primus inter pares—first among equals. Yet, in Akotogbo, my people are robbed of their inheritance while others pretend all is well.

Despite this pain, our people—though grievously wronged—remain committed to peace. Violence is not an option. The elites on both sides, bound by kinship and intermarriage, have chosen dialogue. Autonomy for both sides has emerged as the practical solution. The government must now ratify this compromise for peace to prevail.

Akotogbo, once the economic hub of the Okitipupa/Igbekebo division, has suffered stagnation because of this protracted leadership crisis. Truly, a house divided against itself cannot stand.

As for our departed hero, Oba Simon Olatuyi Odogbo—you gave your all. I commiserate with your children, who bore the brunt of your sacrifices. Many abandoned education because you devoted your resources to endless legal battles, worsened by withheld salaries. Yet you stood firm till the end. Personally, I have lost a father who took me under his wings. I will never forget my visits to you—especially the day I brought my wife and children to the Palace. That memory remains etched in my heart. When Papillo visited early last year, you asked after me. Prince Olanrewaju called me on video—that was our last conversation.

Oh, Lekeleke ti r’elu Ik’efun—the Laba of Akotogbo has departed. Yet the struggle remains unfinished. Kabiyesi, tell Oba Nenuwa Aribo that the leopard no longer roars as of old. Tell Baale Meshe that our lands—from Salawa through Abusoro to Naino and Iyekaawa—are under encroachment. Inform Baale Eraboh that Kojegben, Yopiara, Oposo, and Kesema are threatened. Let Baale Ojowuro know that the stretch from Potogiri through Ijuosun Road, Gbagbaye, to Barogbo is in contest. You were the 12th Laba of Akotogbo—after Okinikan, Ohenwene, Olu, Ojowuro, Eraboh, Apa, Gbenegun, Ogboro, Kulejoluse, Meshe, and Nenuwa.

May the next dispensation be glorious and redemptive.

As a Christian, I rest in this hope: Kabiyesi, we shall meet again on the resurrection morning.

Good night, Sir.